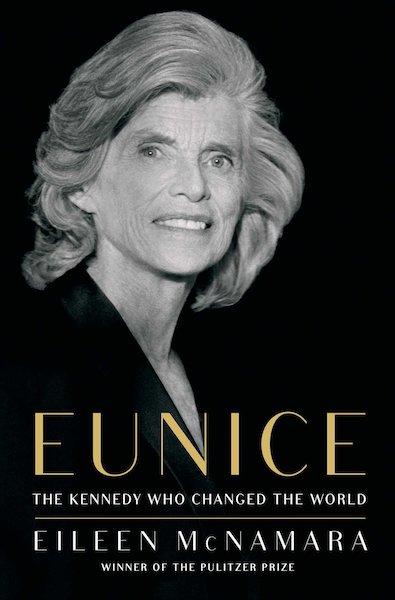

Eunice: The Kennedy Who Changed the World is Eileen McNamara’s new biography about Eunice Kennedy Shriver. Shriver is best known as the founder of Special Olympics, but that monumental achievement is just one of her many contributions to the welfare of children, women, and people living with special needs and disabilities. Recently, I had a chance to ask Shriver’s biographer several questions about what she learned while researching and writing the book.

What piqued your interest in Eunice Kennedy Shriver?

Senator Edward M. Kennedy died two weeks after his sister Eunice in August 2009 and I was taken aback by the photo captions accompanying his obituary in the New York Times. In almost every one, his sisters were misidentified or not identified at all. I had been talking with Simon & Schuster about the astounding fact that a biography had never been written of Mrs. Shriver. The correction the New York Times ran of those captions convinced me to undertake that project. It was clear to me that – in her family and in history – Eunice Kennedy Shriver was invisible or indistinguishable from her sisters. I knew enough about her accomplishments to know that there was nothing invisible about her and that she stood out for her achievements among all the women – as well as the men – in the Kennedy family.

Can you briefly describe how you conducted your research?

It took me a few years to convince the five Shriver siblings that I could be trusted to produce a thorough, complete and honest biography of their mother if they would give me unrestricted access to her private papers, 33 boxes of which were in storage at the JFK Presidential Library in Boston. I understood their reluctance; journalists have not always dealt fairly with the Kennedy family. I pushed because I knew those papers – which her children had not read – would provide insights into the woman she was. I had won a Pulitzer Prize at the Boston Globe and later contributed to the coverage of the clergy sex abuse scandal in the Catholic Church detailed in the Oscar-winning movie “Spotlight.” I am grateful that the Shrivers did trust me with those papers and agreed to be interviewed for the book knowing they would not see the manuscript before publication. I talked as well to scores of Mrs. Shriver’s friends, extended family (including Ethel Kennedy) and colleagues in her lifelong campaign on behalf of people with intellectual disabilities. My interviews took me to London where I met a classmate who sat beside her in Study Hall in the convent school she attended when her father was the US ambassador to Great Britain. I went to Stanford University where she earned her undergraduate degree and to Chicago and West Virginia where she worked with juvenile delinquents and women in federal prison. I logged hours at the National Archives in Washington, learning all I could about the work she did during World War II in the US State Department and after the war in the US Justice Department.

What do you admire most about her?

Her persistence. She knew that no single battle wins a war. She fought all her life for the hearts and minds of lawmakers, presidents and members of the public on behalf of people with intellectual disabilities. When she began in the 1950s, those she championed were warehoused in Dickensian institutions, denied a seat in a public school classroom and a place on the playing field and a job in the community. When she won those rights, she did not stop. She knew that those rights had to be protected so she went back again and again to Capitol Hill to make sure the government kept appropriating money for special education, for group homes, for job training, for medical research. She was relentless because, without vigilance, progress can be rolled back and she would not stand for that.

What about her allows readers to identify with her?

Most of us do not have a 250-acre “backyard” on which to establish a summer camp for children with intellectual disabilities. But in 1962 when Eunice created Camp Shriver on her Maryland estate, she was doing what so many mothers of children with intellectual disabilities were trying to do on a much smaller scale in an effort to help their children enjoy life. Mrs. Shriver used her famous name, her father’s money and her brother’s presidency to kick down doors all over the world on behalf of those children. No one thought she’d succeed. She said toward the end of her life that she was always told by men that real power was not for her. But because she refused to listen to them, she was able to do what no one had ever done before. She got her strength from every mother she saw trying to do her best for her children as her own mother, Rose, had tried to help Rosemary, the older Kennedy sister born with intellectual disabilities. What woman cannot identify with Eunice’s struggle to be seen and heard in her family and in the world?

What would you list as her greatest contributions as a citizen of the world?

She was not satisfied with making progress on this issue in the U.S. alone. In the mid-1980s – when children with intellectual disabilities in places in China, the Mideast, Africa and the Soviet Union – were still being denied their basic human rights, she insisted that Special Olympics become an international movement. Getting children onto the playing fields in those places opened the door to getting them into group homes, into jobs and out of huge residential institutions. She made the world look differently at a child with intellectual disabilities. Where once the world saw the disabilities, she refocused the world’s attention to see the child.

What about her life can encourage parents raising children with special needs today?

Eunice Kennedy Shriver was told “no” all her life but she refused to take “no” for an answer. When she asked President Kennedy to create a National Institute for Child Health and Human Development so that federal funds could help scientists research the causes of intellectual disabilities and other conditions that impact developing fetuses and infants, the president told her that the medical establishment said it did not need such an institute. She said the establishment was wrong. She pointed to the miscarriage and the stillbirth that Jackie Kennedy had suffered in the 1950s as examples of circumstances that needed more research. She got President Kennedy to “yes.” Today that institute is named for Eunice Kennedy Shriver. When she wanted to make swimming a Special Olympic event experts told her the children would sink. “Nonsense,” she said, proving it with the success of young swimmers at Camp Shriver. All her life she counseled parents of children with special needs to trust themselves and their instincts, not the experts who too often are naysayers. She had faith in these children and their parents and now five million in more than 170 countries around the globe prove over and over again that Special Olympians can swim, run, jump, dunk a basketball and hit a baseball as well as any child on the planet.

Where can readers find the book?

At their local bookstore or on Amazon.

Do you like what you see at DifferentDream.com? You can receive more great content by subscribing to the quarterly Different Dream newsletter and signing up for the daily RSS feed delivered to your email inbox. You can sign up for the first in the pop up box and the second at the bottom of this page.

0 Comments